New Method Can Identify What Genes Do, Test Drugs' Safety

May 4, 2006 -- Utah and Texas researchers combined miniature medical CT scans with high-tech computer methods to produce detailed three-dimensional images of mouse embryos – an efficient new method to test the safety of medicines and learn how mutant genes cause birth defects or cancer."Our method provides a fast, high-quality and inexpensive way to visually explore the 3-D internal structure of mouse embryos so scientists can more easily and quickly see the effects of a genetic defect or chemical damage,” says Chris Johnson, a distinguished professor of computer science at the University of Utah.

A study reporting development of the new method – known as “microCT-based virtual histology” – was published recently in PLoS Genetics, an online journal of the Public Library of Science.

The study was led by Charles Keller, a pediatric cancer specialist who formerly worked as a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of University of Utah geneticist Mario Capecchi. Keller now is an assistant professor at the Children's Cancer Research Institute at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

University of Utah co-authors of the study are Johnson – who directs the university"s Scientific Computing and Imaging Institute – Capecchi, medical student Mark S. Hansen and several members of Johnson’s institute: computer science undergraduate Thomas Johnson III, research assistant Lindsey Healey and former associate director Greg M. Jones, who now is state science advisor to Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman Jr.

Scientists often use mouse embryos both to learn what genes do and to test the safety of new drugs and household chemicals. By disabling or “knocking out” a gene, researchers can see what goes wrong in the mouse embryo and thus learn the gene’s normal function, or learn how a mutant gene can cause cancer. Mouse embryos also are sensitive to toxicity from chemicals, so new medicines and chemicals are tested on them to see if any defects develop, indicating the safety for humans and their unborn embryos.

But the traditional method of histology – the anatomical study of the microscopic structure of living tissues – has been difficult and time-consuming. Mouse embryos with genetic mutations or damage from toxic chemicals are killed, embedded in wax, sliced into thin sections, then stained and placed on slides for examination under a microscope.

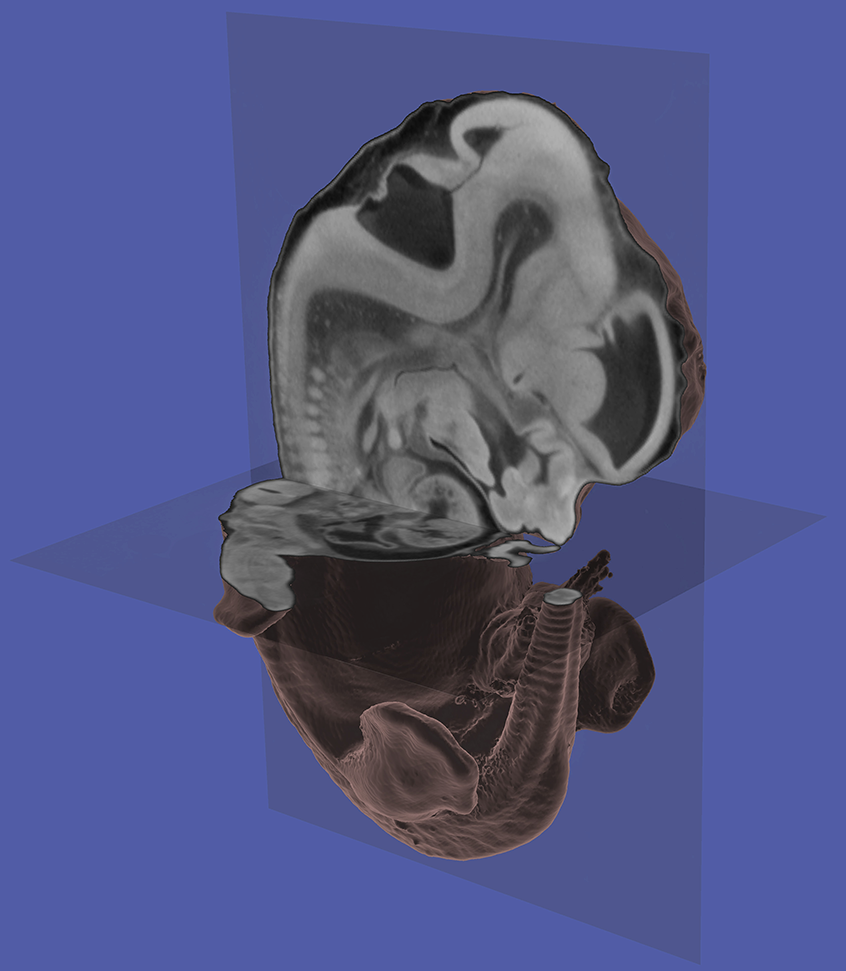

The new, faster and inexpensive method is called “virtual histology” because it uses computer visualization techniques to convert X-ray CT scans of mouse embryos into detailed 3-D images showing both the mouse’s exterior and interior.

Instead of being sliced up physically, mouse embryos are stained with special dyes. Traditional CT scans take a series of X-ray images representing “slices” through the body, and they primarily “see” bone and other hard tissues such as cartilage. In the new microCT virtual histology, the special dyes permeate the skin and other membranes, which are still permeable in an embryo.

“This technique allows us to get at a lot more tissues other than bone, such as internal organs, which [conventional] CT scans can’t pick up,” Johnson says.

Johnson and his team wrote a computer algorithm – a problem-solving formula in computer software – to take the CT scan data and automatically distinguish various organs and structures in the mouse embryo. The “virtual rendering” of the CT scan data also includes a virtual light source so the 3-D embryo image includes shadows that make it easier for the human eye to understand and interpret the image.

The embryo images can be made transparent or have cutaways so that internal organs and body parts are visible. And the detail they show is exquisite – revealing features as small as one-tenth the thickness of a human hair.

The idea is to allow geneticists to quickly examine large numbers of embryos, each with a different gene disabled, so that the normal function of many genes can be determined faster than with existing methods.

Keller says the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Environmental Protection Agency require drug and chemical manufacturers, respectively, to test their new products, but that such tests often are subjective. The new method “allows chemical and drug companies to conduct these studies in a much more quantitative way, improving upon the safety of the products we find in our homes,” he adds.

Keller and a colleague have founded a company named Numira Biosciences, which plans to make the virtual histology method available through the sale of kits and imaging services.

The study was published online in the April 28 issue of PLoS Genetics.

The complete study, with more images of mouse embryos, is at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0020061.