Most farmers probably never thought they'd be in the market for a way to process huge digital images more quickly -- until, that is, inexpensive drones with high-resolution cameras gave them access to images they could use to micromanage irrigation and to detect the growth of crop-threatening diseases.

Most farmers probably never thought they'd be in the market for a way to process huge digital images more quickly -- until, that is, inexpensive drones with high-resolution cameras gave them access to images they could use to micromanage irrigation and to detect the growth of crop-threatening diseases. When farmers use drones to gather data about their crops, they usually send out a drone operator to scan the fields, bring all the imagery back to the office, download it to a computer and then upload it to the cloud. All that takes time. "So you're 24 hours out before you get to see your data," said Amy Gooch, CEO of ViSUS, a Utah-based company. "We are trying to make it so that you can see your data right there in the field."

A spinoff from the University of Utah's Scientific Computing and Imaging Institute, ViSUS -- "visualization streams for ultimate scalability" -- is developing data-streaming techniques for progressively processing and displaying ultra-large image files from drones scanning crops to visualizing complex connections between neurons in the brain.

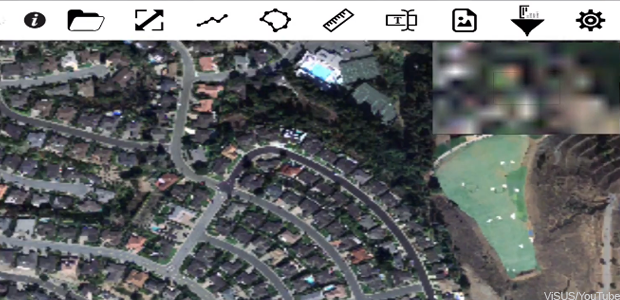

The company's ViSOAR Ag Explorer stiches the drone images together to generate a map, then renders it for an iPhone, iPad or monitor. "It only renders the amount of data that you have the screen space for," Gooch said. That's how the software can deliver results immediately, and on commodity hardware, without loss of resolution. "It only fetches the amount of data it needs at the moment," said Gooch. "It is progressively refining, and as you zoom in it goes and fetches more data."

ViSUS stores the images in a raw data format that enables efficient, streaming pipelines that process the information while it's in movement. Users can manage large datasets in real time on a variety of commercial platforms – from desktops to iPhones. ViSUS has been deployed in a variety of large data applications such as the monitoring of large scientific simulations and the editing of massive images and panoramas, the company said.

The ViSOAR app allows users to browse a range of gigapixel images, add annotations (polylines, polygons, measurements lines, text, images) and adjust the imagery's brightness, contrast, hue and saturation on the fly.

The approach is hierarchical, loading images of increasing resolution as the user clicks to see more details.

"It's a little like Google Maps, where you zoom in and in. Except with our technique, you don't reload all the data each time," said Valerio Pascucci of the SCI Institute at Utah, where the technology was developed. "You only download the differences between levels, so it's faster and requires less memory," he said.

The ViSOAR Ag Explorer team is also developing analytic tools, including multispectral and time-series processing that allows for pixel-value differencing over time.

According to the team, the quick turnaround of imagery coupled with the analytic tools will allow farmers to optimize the use of fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides, as well as to spot potential problems, such as diseased plants, standing water and irrigation problems.

ViSOAR Ag Explorer is being developed with a grant of $150,000 from the National Science Foundation under the Small Business Innovation Research program. According to Gooch, the team expects a beta version of ViSOAR Ag Explorer to be available within a year and a release version to be deployed within two years.

The video demonstrates some simple image processing, computed on the fly, on a 74.25 gigapixel image of San Francisco.

Article originally appears on GCN

Article originally appears on GCN